Note: This is Part 1 in a 3 part series on Morocco.

“Before Marrakech, everything was black. This city taught me what colors are and I embraced its light, its bold contrasts, and its intense inventions.”

— Yves Saint Laurent

For centuries, Morocco has enticed travelers the world over with its exotic beauty. Romanticized in classic movies like Casablanca and celebrated in songs like Marrakesh Express, Morocco is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the world; yet the country still manages to maintain an air of mystery.

Like so many others, I was intrigued by this unique land, and when I found an affordable flight to Marrakech for Winter Break, I jumped at the opportunity. I had thought about going during Spring Break last year but that was during Ramadan, when Muslims fast during the day and many restaurants are closed. It seemed like an awkward time to visit, and summer is just too hot. If Baltimore summers make me want to hide in my air conditioned house for 3 months, I know I couldn’t handle Moroccan summer, when temperatures frequently soar into the triple digits.

Moroccans will tell you it gets cold there in the winter, but compared to the northern U.S., that’s not really true. Rarely does it get below 40 degrees Fahrenheit, and during the afternoon it’s often closer to 60 and can feel much warmer than that in the sun. It’s true that temperatures tend to swing wildly, especially in the desert, but as a resident of a state that can never make up its mind about what season it is, I’m pretty much used to that. Overall, the weather was very pleasant most of the time, with the added bonus that there were very few bugs.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Morocco has a long and fascinating history that I can’t possibly do justice to here, but I will attempt to give a broad outline.

Morocco is located in Northwest Africa, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean. Morocco also marks the northern edge of the Sahara desert and is at the heart of the region known as the Maghreb. Although the indigenous Berber peoples have lived in what’s now Morocco for many thousands of years, the recorded history of Morocco begins around the 8th century BCE when the Phoenicians colonized the area. The ancient Greeks considered Morocco to be the edge of the world, and a legendary Moroccan king, Atlas, features prominently in Greek mythology. Famously, Atlas was condemned to hold up the world for all eternity. It is from the name of this mythological figure that not only the name of Morocco’s Atlas Mountains is derived, but also the Atlantic Ocean and the word for a collection of maps.

In the 5th century BCE, Morocco was ruled by the ancient city-state of Carthage. After Carthage’s defeat in the Punic Wars, Moroccans founded their own kingdom called Mauretania (not to be confused with the modern nation of Mauritania), which encompassed most of modern-day Morocco as well as a large area of Algeria. At times Mauretania was a vassal state of the Roman Empire, but it was never fully assimilated and the kingdom continued to survive for centuries after the fall of Rome.

In the 7th century CE, the Islamic Expansion spread to Morocco. Morocco became part of the new Islamic empire, the Umayyad Caliphate. Most people converted to Islam and the Arabic language was introduced (along with immigrants from the Arabian peninsula, who became the new elite), but Morocco held onto many of its own laws and customs. Around this time we see some of the first distinctions being made between the “Berber” and “Arab” populations of Morocco, which will continue to be a source of contention all the way to the present day.

On the surface, the difference would seem clear: The Berbers were the original indigenous inhabitants of Morocco and the Arabs were people from Arabia in the Fertile Crescent, who invaded/settled in Morocco in the 7th century. However, the reality is a little more complicated. First of all, there is no single distinct ethnic group called the Berbers. The word “Berber” may derive from the Arabic word for “barbarian” and is used as an exonym by outsiders to describe members of a wide range of peoples known more properly as the Amazigh. Amazigh cultures are spread out all over the Maghreb and beyond and the main thing they have in common is that they speak languages that are related to each other but that are nonetheless often mutually unintelligible. Because many Amazigh peoples have traditionally led nomadic lifestyles, it is difficult to define borders between different groups. Moreover, when Arabs settled in Morocco, they intermixed with the local population, making it next to impossible to determine who truly has “Berber” ancestry and who has “Arab” ancestry.

The early Islamic governments of Morocco practiced something of a double standard when it came to ethnicity. Officially, they upheld the Quranic principle that all Muslims were equal in the eyes of God and that background did not matter as long as you were of the faith. Unofficially, people who could trace their family line back to the first generation of Arab settlers and especially those who could claim to be descendants of the prophet Muhammed himself, were often seen as superior and tended to receive preferential treatment. Those who identified as Arabs sometimes accused “Berbers” of embracing a form of Islam that was less pure. The truth is that claims of ancestry from Muhammed or one of his first disciples were often unfounded and such claims are usually not considered to be proof of “Arab” ancestry by modern historians. To further confuse matters, the Christian kingdoms of Iberia who were being rapidly conquered by Islamic forces, referred indiscriminately to all the Muslim invaders as Berbers or “Moors”, regardless of their origins.

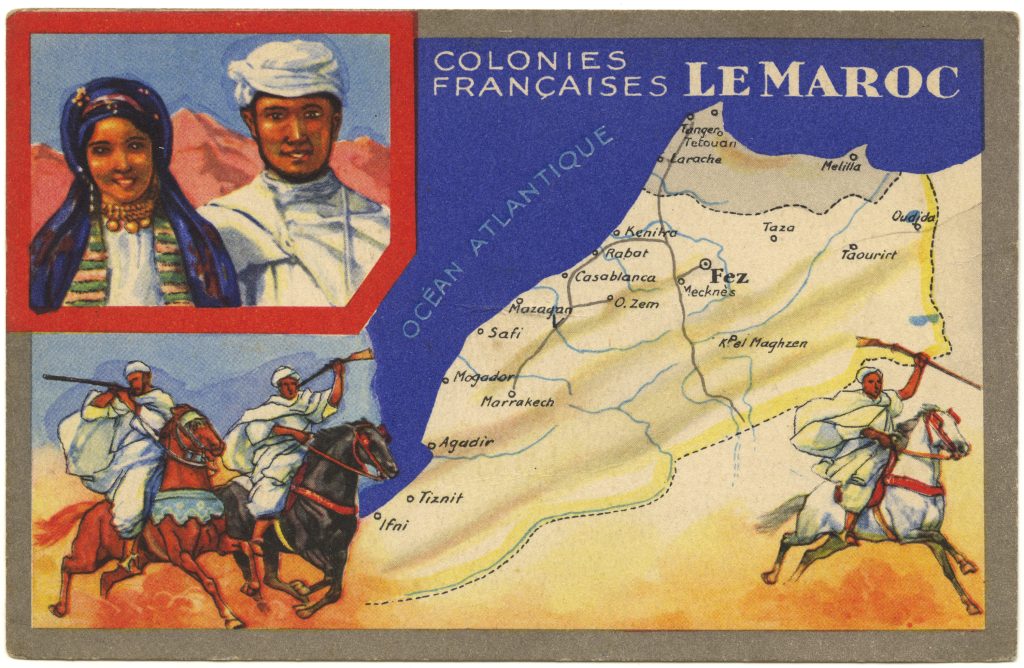

Much later, under French colonialism, the French tried to impose European concepts of race on Moroccans and divided Moroccans into three artificial categories: Arabs, light-skinned Berbers, and dark-skinned Berbers. The French saw these three categories as a natural racial hierarchy and treated them accordingly, discriminating against them in distinct ways and attempting to segregate them. Fortunately, post-colonial Morocco has by and large rejected this form of racism and there is a strong patriotic emphasis on unity among all Moroccans. At least, that is what is voiced publicly. As an outsider, it’s hard for me to gauge the sincerity of this sentiment. At any rate, being “Berber” or “Arab” is mostly a matter of identity these days. Amazigh cultures are protected under Moroccan law and there are efforts being made to ensure the preservation of Amazigh languages and other cultural traditions. Amazigh is now one of two official national languages of Morocco, alongside Arabic. (French is also commonly spoken here in addition to Moroccan Arabic which differs significantly from the official standard Arabic.) Surveys show that Moroccans living in rural areas are more likely to identify as Berbers, whereas urban Moroccans are more likely to identify as Arab. However, DNA tests have shown that genetically rural Moroccans tend to have more Arab ancestry than urban Moroccans, underscoring the reality that these categories today are largely cultural, not genetic.

With all that being said, the division between Arabs and Berbers did play an important role in the early Islamic period of Morocco. Chafing under the rule of the increasingly rigid Umayyads, the Berbers revolted in 740 CE and gained their independence. For a time, Morocco was fractured into several different provinces and fell victim to internal political turmoil and intrigue. Nonetheless, this period saw the creation of some of Morocco’s most important mosques, schools, and shrines. Moroccan cities were connected to the ever-expanding Islamic Trans-Saharan trade networks as well as to Al-Andalus (Muslim Spain and Portugal) and the wider Muslim world. Then, in 1060, the Berber-founded Almoravid dynasty united all of Morocco into one coherent state. In 1070, the Almoravids founded the city of Marrakech near the edge of the Sahara desert as the capital of their new empire. As Ibn Idhari wrote in Al Bayan al Mughrib, “Our choice was made for this Saharan site where gazelles and ostriches are the only companions and where only thorny and coloquitous plants grow.” (“Coloquitous” refers to a bitter wild desert fruit that is not safe for human consumption.)

Due to its remote location deep in the nomadic hinterlands, Marrakech was destined to became the most distinctly “Berber” of Morocco’s four imperial cities (the other three being Fes, Meknes, and Rabat–the current political capital of Morocco). Even today it retains a distinct desert vibe that sets it apart from other Moroccan cities. Guides for Western tourists often warn readers that visiting Marrakech for the first time will be a huge culture shock and that it is totally alien to the concept of a Western city. I found those warnings to be grossly exaggerated and honestly kind of racist. Marrakech is a city with streets and addresses, post offices, shops, restaurants, houses, schools, parks, taxis, bikes, and all the things you would expect in any other city in the world. Even in the Medina you can use Google Maps with a surprising degree of accuracy to find your way around. And for better or for worse, Marrakech has become a massive tourism hub with all the features that come along with that. That said, Marrakech is still one of the most unique cities I’ve ever been to, and I’ve been to a lot of interesting cities all over the world.

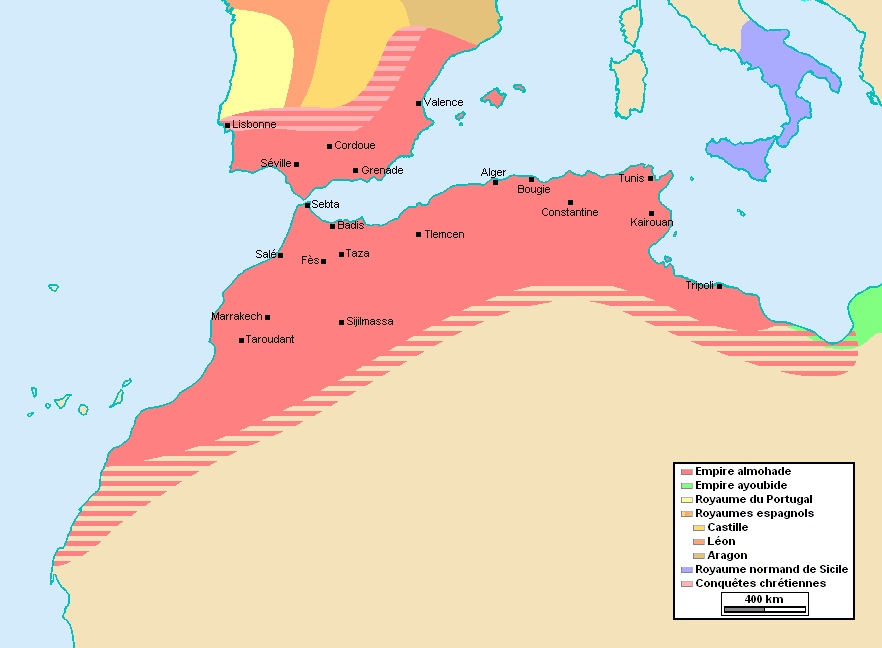

Getting back to our history, in 1129, the Almoravid dynasty gave way to an even more powerful Berber empire that ruled most of North Africa and Iberia, the Almohad caliphate. With control of territories from Lisbon to Tripoli and beyond, Morocco was at the height of its power. The Almohads thrived for over a century until the Spanish Reconquista finally caused their collapse in the 1200s. The next dynasty to rule Morocco were the Maranids, also of Berber origin, although they claimed Arab ancestry through a remote lineage. Although they ruled Morocco for centuries, their attempts to reunite the Maghreb and Al-Andalus were unsuccessful and in the 1400s they descended into civil war. They were succeeded by the Wattasid dynasty and then the Saadi dynasty, whose colorful tombs can still be visited in Marrakech.

Next came the short-lived but exciting Barbary pirate republic of Sale’ which terrorized the Mediterranean coast from 1624-1668. The story of the Barbary pirates–an unprecedented alliance of Ottoman corsairs, European rebels and outcasts, and Muslim and Jewish refugees from Spain–is absolutely fascinating and deserves its own blog. Unfortunately, I don’t have time to get into the details here.

In 1666, the Alawi dynasty, which still rules Morocco to this day, was founded. Claiming descent from Muhammad, the Alawi family consolidated their control of Morocco with an army of slaves and reclaimed Tangiers and the Mediterranean coast from England and Spain. In 1777, Morocco became the first country to recognize the United States as an independent nation. This was an attempt by the Alwais to regain relevance on the world stage, but unfortunately the attention they garnered was not the kind they wanted. After a piracy incident led to an invasion of Morocco by the brand new American republic, Morocco’s weakness was revealed to the imperial powers of Europe and the Ottoman Empire who were always hungering for new colonies or vassal states. Although it managed to nominally maintain its independence, Morocco was attacked by Spain and France, and forced to give concessions to Britain and go into debt.

The French and Spanish continued to encroach on Morocco and the country was occupied as a “protectorate” from 1912 to 1956. During this time, half a million Europeans settled in Morocco, concentrating in the coastal city of Casablanca. There was also a mass migration of Morocco’s significant Jewish population from the interior to the coast, seeking opportunities for trade with the Europeans. In addition to the racial policies I described earlier, the French and Spanish colonizers exploited the mineral riches of Morocco and its vast agricultural lands. Resistance to colonial rule bubbled up in many different times and places, sometimes organized, sometimes taking the form of spontaneous riots. After World War 2, independence movements gained momentum across North Africa. While Morocco did not experience the level of intense guerilla warfare that nearby Tunisia did, the French government took numerous actions to ruthlessly suppress dissent in Morocco. One of these measures proved to be their undoing. By forcing the highly respected Sultan Mohammed V (who was considered by many Moroccans to be a religious leader as well as a political one) into exile, the French caused Morocco to erupt in violence, forcing them to return the sultan and to negotiate terms of independence for Morocco in 1956.

In the decades following Morocco’s independence, the government focused on “Moroccanization”, where French-owned assets in Morocco were transferred to Moroccan loyalists of King Hassan II (Mohammed V’s son). During this period Morocco was a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary elections were held, but accusations of corruption led to political turmoil. A decades-long conflict with Spain over the disputed territory of Western Sahara went a long way towards uniting Moroccans behind a patriotic cause. In 1976, Spain ceded control of the region to Morocco and neighboring Mauritania but a separatist faction has taken root in Western Sahara, proclaiming the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic. which is not recognized by Morocco or most other nations. Morocco’s military has been engaged in conflict with the Saharawi rebels off and on ever since, and it has also led to conflict between Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria.

In 1999, the more liberal Mohammed VI ascended the throne. Mohammed, who is still the King of Morocco today, has undertaken many efforts to modernize the country. He has instituted free elections, released thousands of political prisoners, granted more rights to women, introduced the teaching of Amazigh language in all public schools, and pursued free trade agreements with Europe and the United States.

In 2003, a series of terrorist attacks by Islamic fundamentalists plagued Morocco. During the Arab Spring uprising of 2011, mass protests and a deadly bombing took place in Morocco, and the King conceded to a referendum that put major limitations on the power of the monarchy.

In 2022, Morocco became the first African nation to reach a semi-final match at a World Cup soccer competition, defying expectations. After defeating Portugal and Spain, they ultimately fell to their former colonizer, France. The underdog team’s impressive performance has been a source of great pride in Morocco and is seen by some as a symbol of Morocco’s rising status in the world.

On September 8th, 2023, a 6.8 magnitude earthquake hit Morocco, killing nearly 3,000 people, injuring thousands more, and creating a humanitarian crisis in the remote mountain villages southwest of Marrakech where the earthquake’s epicenter was located. Despite this tragedy, Morocco continues to welcome tourists from all over the world. Tourism is one of Morocco’s main sources of income and in the wake of the earthquake, they rely on that revenue more than ever.

ARRIVING

I got to Morocco by taking a direct overnight flight from Washington-Dulles International Airport to Casablanca with Royal Air Maroc. I had read some terrible reviews of that airline so I was a little trepedatious at first, but it turned out fine. From Casablanca, I took a domestic flight to Marrakech. As the plane descended and we flew over row after row of square-shaped red adobe buildings, I could already see why Marrakech is called the Red City. After retrieving my luggage, I withdrew some money in the local currency, Moroccan Dirhams or MAD. One American dollar is worth about 10 MAD, so it was easy to get a handle on prices.

Outside the Marrakech airport, there is a taxi stand where you can hail a taxi. They had standard prices that are posted for everyone to see, which took away some of the anxiety one has when first arriving in a new country. There are a number of taxi scams in Morocco that I read about and this system helps travelers avoid them. It was still a little more money than what a non-airport taxi in Marrakech would cost for the same length of trip, but taxis are cheap in Morocco and even this taxi was still only about $8.00. In the taxi, I passed through the modern part of the city before arriving at the gate of the medina. From here I would need to continue on foot, as cars cannot enter the medina.

For those who are unfamiliar with the concept of medinas, a medina is a walled citadel, common in older cities in Muslim North Africa. The medina is often the oldest part of a city. The medina in Marrakech is a maze of narrow streets and alleys packed with throngs of people, donkey carts, motorcycles, and products for sale. The main thoroughfares of the medina are lined with endless shops and outdoor vendors hawking everything imaginable, from spices and fresh olives to bejeweled Berber daggers and bootleg Louis Vuitton bags. While many of the wares offered are primarily for tourists, the majority of shoppers in the medina are locals, and there is something for everyone here. There is both treasure and trash aplenty in the medina, and it’s sometimes hard for outsiders like me to tell which is which and what is a fair price. Most products don’t have price tags as haggling is the norm here and obviously tourists are charged a higher price. At the same time, because of the vast difference in currency values, An American dollar will buy far more here than it would in the U.S. or Europe. So I often felt that in an odd way I was both being ripped off and ripping the seller off at the same time. As a newly arrived American tourist hauling my luggage, I stood out like a sore thumb here, and some of the vendors called out to me or walked alongside me asking me questions to try to engage me so they could sell me something. It was a little overwhelming since I was still trying to find my riad and unload my luggage, but repeating no or “non, merci” a few times was usually enough to get people to leave me alone.

Eventually I got to a quiet side alley that would take me to my riad. Up until now, Google Maps had served me surprisingly well, but finding the right building was now proving to be a challenge. I found a sign advertising my riad but it was on an overhanging structure and I still couldn’t locate where the entrance was. At this point, a couple young men approached me and asked me where I’m staying. Now, I had read up on common scams before I got to Morocco and I knew that people often approached tourists offering to show them somewhere only to then demand money. I tried to avoid talking to these guys, but there was no-one else there and they kept pestering me. As soon as they figured out which riad I was looking for, they immediately dashed down an even smaller alleyway and beckoned excitedly for me to follow them. I could see that it was indeed the right place, but I purposely walked in other directions first and then slowly made my way there while avoiding any eye contact with the two youths. It was to no avail. They were already knocking on the door of the riad. They tried to take my bags for me but I insisted on carrying them myself. I entered the riad and talked to the host, trying to ignore the two young men, but they wouldn’t go away. They talked to the host in Arabic and he told me that I need to give them some money because they helped me find the riad. I explained to him that I didn’t ask for their help but in the end it was clear that they weren’t going away until they got paid and my host was not willing to try to force them to leave. For 50 MAD ($5.00) they left me alone and I never saw them again. The host was somewhat apologetic afterwards but I basically learned that sometimes you can’t avoid getting scammed even when you know it’s happening, especially when you’re travelling alone. It was irritating at the time, but I never felt like I was in any real danger.

Now that that little drama was over, I could finally relax. As I waited for the host to get my room key, I got my first taste of the ubiquitous Moroccan mint tea (AKA “Moroccan whiskey”) that is an essential part of practically every single social interaction in Morocco. Often served with a cube of sugar, occasionally without, but always with a sprig of fresh mint, it is unfailingly delicious and refreshing. Every Moroccan, from the King down to the poorest nomadic hut-dweller, keeps a pot of mint tea at the ready at all times. If you enter someone’s home or place of business in Morocco and they don’t offer you mint tea, it means you’re not welcome. I love tea and I especially love Moroccan mint tea, even the vastly inferior mass produced kind you can get in the States. I was served so much mint tea in Morocco that even I temporarily got sick of it, but after skipping it for 24 hours I was more than ready to return to its warm embrace.

As I sat sipping my mint tea, I started to take in the details of the riad. A riad is traditional rectangular house, usually found in the medina. Riads always have a central courtyard, usually richly decorated with colorful tiles, a fountain or pool, and often a garden of some kind. Most riads are two or three stories tall and often feature an open roof above the courtyard and a rooftop patio above the rooms. Many riads were once single family mansions owned by the rich, but most are now guest houses that visitors can rent for the night. The prices are comparable to modern hotel rooms outside of the medina and what they lack in spaciousness and modern touches they more than make up for in style, beauty, and comfort. They are usually locally owned by a family and there are typically only 5-10 rooms, so there is a personal touch. They usually serve food, and both the food and service I received at this Riad as well as the one in Fes, were exceptional.

After relaxing in the riad for a little while, I set out to explore the medina. I followed the narrow alleyways through market after market and eventually made my way to the main plaza, Jemaa el-Fnaa. This large open area is a massive outdoor marketplace and performance space. It has been around in some form or another for about 1,000 years, and has been home to many festivals, parades, and–long ago–public executions. Today it’s a place where you can purchase all manner of things. They even have snake charmers and dancing monkeys, which I avoided for obvious ethical reasons. In the evening, the plaza transforms as hundreds of tables and tents are set up and cheap Moroccan food is served. Although many of the restaurants that border the plaza are quite affordable by American standards, they’re still pretty steep for many Moroccans. By contrast, the food served at these outdoor popup cafeterias is priced for working class Moroccans, who flock here every evening. My understanding is that after dark, things can get pretty wild in Jemma el-Fnaa, especially in the summer, but while I was there, it was fairly tame, snakes and monkeys not withstanding.

I ate a very tasty dinner of couscous and vegetables at the acclaimed restaurant, Nomad, located on the edge of Jemma el-Fnaa. The restaurant has rooftop dining with a great view of the plaza and the medina. Before I went to Morocco, I was a little apprehensive about finding vegetarian food there. While I knew that Moroccans eat a lot of delicious plant-based foods, I also read that a lot of restaurants might not be overly familiar with vegetarianism and that many dishes that seem like they would be vegetarian are actually cooked with meat stock. However, I found that there are a great many restaurants in both Marrakech and Fes that have specifically vegetarian sections of their menus and take care to cater to the needs of vegetarians. There are even vegan and vegetarian restaurants in Marrakech (perhaps no surprise since the city is popular with hippies the world over) but I didn’t go to those. But since this was my first meal in Morocco, I was still a little guarded, and when I received a plate of couscous with a large steak-shaped slab on top, drenched in sauce, I had to ask the waiter what it was. Turns out–it was pumpkin! And quite good too. My health nut sister will be happy to hear that Moroccan cuisine is teeming with robust locally-grown organic vegetables. And because they’re cooked with Moroccan spices, they’re usually pretty tasty. To wash down my meal, I of course had some mint tea. Mint tea is almost always served in a small clear glass that looks like a shot glass (hence the nickname, Moroccan whiskey). At Nomad, they gave me my own little tea pot so I could pour out one shot of tea at a time without the rest getting cold.

EXPLORING THE RED CITY

The next morning I got up on the early side and ambled down to the central courtyard of my riad. They hadn’t finished making breakfast yet, but there was some very good bread and Moroccan pancakes (which are thicker than French-style crepes but softer and more porous than American pancakes), and I managed to procure a cup of coffee before heading out. The streets of the medina felt very different in the early morning, almost abandoned compared to the elbow to elbow crowds I had experienced the previous day. I still had to occasionally duck out of the way of a motorcycle, but overall, a much calmer and quieter experience.

My first stop of the day was the Saadian tombs, where members of Morocco’s royal family from the late 1500s and early 1600s are buried. Many of the tombs have been well-preserved and are decorated with a distinctive colorful tile pattern. The walls and ceilings of the grander tombs are also richly decorated with very intricate relief sculptures and mosaics. I love Islamic art because Islam’s restrictions on depicting people in art have forced Islamic artists to be very creative and the geometric designs they come up with are usually quite beautiful to me. There was one section of the Saadian tombs that was closed because of damage from the earthquake. This was the first example of earthquake damage I would see in Marrakech, but not the last.

After the Saadian tombs, I visited the ruins of El Badhi palace, which translates to “The Palace of Wonder/Brilliance”. This palace was built in 1578 for the Saadi sultan Ahmad al-Mansur, to show off his wealth and power. The sultan wanted to match or exceed the splendor of the old Andalusian palaces of Islamic Spain. He spared no expense, commissioning specialists from Italy to Mali to bring his grandiose vision to life. Today the palace is in ruins–a home to birds and stray cats–but it still evokes that sense of wonder that its name implies. At the center of the palace is a very large courtyard, most of which is taken up by a now-empty pool. There is an island at the center of the pool and a walkway to get from one side to the other. In one corner of the courtyard, there is a grove of lemon trees, with plenty of lemons on them even in late December. Inside the palace, you can see historic artifacts and a video about the palace that includes a CGI rendering of what it looked like in its glory days. This palace was one of my favorite places in Marrakech, perhaps because there were very few people there at the time and I felt fully immersed in this fascinating ruin.

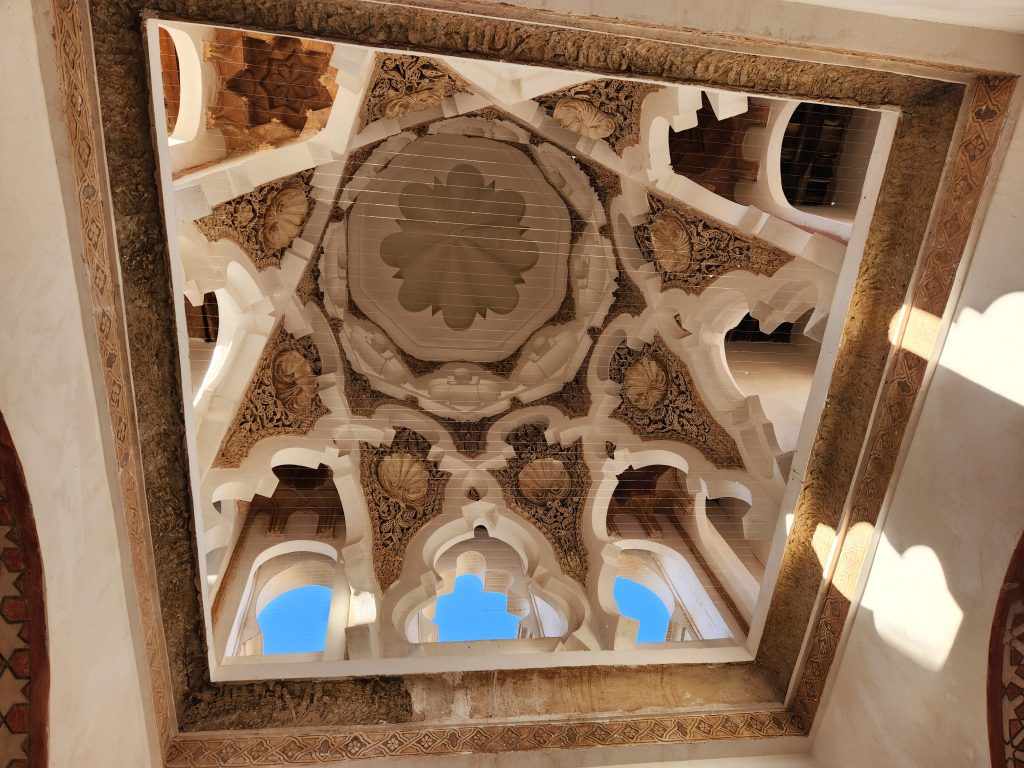

Next was the Bahia palace. Temporarily closed in October and November due to damage sustained from the earthquake, it was open for business when I was there and unlike El Badhi, it was full of visitors. The Bahia Palace is a much more recent construction than El Badhi, only dating back to the late 1800s. That also means that it in much better condition. What this palace lacks in antiquity, it makes up for with its fully intact lavish decor. From classic tilework and fountains to painstakingly intricate ceilings, the Bahia is a site to behold. Outside the palace is a nice tree-lined park with benches, a perfect place to rest in the shade for a few minutes before venturing on to your next destination.

My next destination, as it turns out, was the Jewish Quarter or Mellah, and the Salat Al-Azama Synagogue. Constructed in 1942, this modest synagogue was built on the site of a much older one that no longer exists. That older synagogue was constructed in 1492, the year that Jews and Muslims were expelled from Spain by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella (yes, the same Ferdinand and Isabella who funded Christopher Columbus’ trans-Atlantic voyage in that very same year).

The history of Judaism in Morocco is a long and complicated one, and I am by no means an expert. There has been a Jewish presence in Morocco for thousands of years, since pre-Islamic times. Jews have always been a minority in this country but have played a significant role at times. Jewish culture among the nomadic Berber tribes may have looked a lot different from Jewish lifestyles in other parts of the world. When Jews were forced out of Spain in 1492, many of them fled to Morocco. Many of those Jewish refugees had been living in the Islamic kingdom of Al-Andalus before it was re-conquered by the Christian kingdoms of the north, and it likely seemed only natural to go where their Muslim Marisco neighbors were going. Whatever conflicts had existed between them, there may have been a sense of solidarity between the Muslim and Jewish Andalusians, both cast out at the same time and for the same reason (i.e. not being Christian). This is not to say that Jewish people have always been embraced in Morocco. At various times, some Moroccan rulers and the general population have persecuted Jews to a greater or lesser extent. Sometimes the word “Mellah” is translated as “ghetto”. Yet this is also not a complete picture of the Jewish experience in Morocco. Many Jewish people have thrived here over the centuries and even found refuge here, and they are an important part of Morocco’s rich cultural tapestry. After the foundation of Israel in 1948, the vast majority of Jewish Moroccans moved to that new nation. Today, there are very few Jews left in Morocco. When i was in Fes, I met a shopkeeper who claimed to be the last Jew in Fes. He was also planning to move to Israel within a year.

In Marrakech, at least, there are still a few Jews left. One of them is the long-bearded rabbi who chanted prayers from the center of the synagogue while I was there. It is still an active place of worship. Outside the worship area, there is a small museum with artifacts/relics and photos of Jewish Moroccans throughout the years. There’s also a courtyard with a fountain, very much in the traditional Moroccan style, but the pattern on the tile walls is the 6 pointed Star of David, not the 8 pointed Moroccan star (sibniyyah) you might find anywhere else in Marrakech.

The Mellah is one of the oldest neighborhoods in the Medina, and indeed, in Morrocco. Unfortunately, it was badly damaged in the earthquake. This is one of the few areas where I saw large piles of rubble from buildings and walls that collapsed during the disaster. The ancient houses that are still standing are propped up by 2 x 4s. I hope that this historic neighborhood is preserved, because it’s one of a kind.

After visiting the Mellah, I ate lunch at the Henna Art Cafe, not too far from my riad. I had a hearty meal of lentil soup and a lentil crepe with some mint tea.

The next stop on my itinerary was Mederasa Ben Yusef. This incredible school was built in 1564-65 at the behest of Saadian sultan Abdallah al-Ghalib. At the time, it was the largest Islamic university in the Maghreb, attracting prominent scholars from the fields of religion, philosophy, medicine, and mathematics.

The architecture of the Mederasa is simply amazing. While the student dormitories are small and sparsely decorated except for the windows, the common areas are elaborately decorated with ceramic tiles, sculpted plaster, carved wood, calligraphy, and more. At the center of the campus is a large courtyard with a pool. On either end of the courtyard there is a grand archway. The interior rooms on the second floor overlook the courtyard. The painstaking attention given to the construction and preservation of this school underscores the importance of education in Moroccan history.

Near the Mederasa is another impressive structure, the Qubba or Kouba. This 12th century domed monument is the only surviving Almoravid structure in Marrakech. Historians believe that it was that it was a pavilion used for ritual ablutions before prayer. It most likely belonged to the nearby Ben Youssef Mosque, which was the main mosque of the city at the time. Next to the Qubba there used to be a fountain or water source for another structure. The water flowed through bronze pipes from a nearby cistern covered by a barrel vault, which is still there behind the Qubba. This water delivery system was made possible by an ingenious Moroccan drainage system called khettaras, providing an abundant water source for the city despite the arid environment.

After checking out the Qubba, I next visited the Marrakesh Museum. This Museum bears witness to the history, culture, and art of Marrakech. The building itself is a stunningly beautiful palace built at the turn of the 20th century for the favorite vizier of Sultan Moulay Abdelaziz. Its exhibits include Berber jewelry, ancient Moroccan pottery, contemporary Moroccan art, and much more. A master calligrapher is on hand to paint your name or the name of a loved one in beautiful Arabic script over a Moroccan landscape background that he also hand painted. You can sit next to him and watch him paint or you can visit the exhibits and then collect the finished product.

By now I had been doing a lot of walking, and I had worked up an appetite. I sated that appetite on the scenic rooftop of Cafe Des Epices. In the mood for a traditional Moroccan meal, I ordered a tagine, Morocco’s national dish of stewed vegetables traditionally cooked in a special type of clay pot with a cone-shaped lid. Tagines can be made with a variety of meats, but of course I ordered vegetarian tagine. The meal was good, but if I had realized how much tagine I was going to be eating over the course of the next week, I probably would have ordered something else. The best thing about the restaurant was the excellent view of the city and the Atlas Mountains beyond it.

After dinner, I visited Jemma el-Fnaa again and did some shopping in the medina.

That night in my riad, there was a Christmas Party going on. It was Christmas Eve, and even though most Moroccans don’t celebrate Christmas, a lot of the international guests at the riad did. There was a small Christmas tree in the courtyard and even a little stocking on my door. The host had explained to me by email before the start of my trip that there would be a special Christmas dinner that I could make reservations for. The cost of that dinner was a whopping 85 Euros per person, an enormous amount of money for a meal in Morroco. I had politely declined. What my host failed to adequately communicate to me was that this was not a mere dinner, but a full on Christmas party with live music and dancing. It seemed that all the other guests had made reservations for the dinner, because the courtyard was packed. When I came in, the host actually offered to let me partake in the dinner for free, which was extremely generous, but I had just eaten. However, my room happened to be located directly behind the performers. So I was able to listen to the music and even watch through a window from the comfort of my room. They played traditional Moroccan folk music and then there was a DJ who played some kind of pop music, mostly in Arabic I think but with a couple English songs thrown in too.

(MO)ROCKIN’ THE KASBAH

The next morning was Christmas Day. Sadly, Santa had not filled my tiny stocking, which was pretty lazy of him considering how easy it would have been to park his reindeer on the flat rooftop patio of the riad and climb down the wall of the open courtyard.

I got up early again this morning, so I could get to Jardin Majorelle when it first opened. Located far from the medina in the modern part of Marrakech, Jardin Majorelle (Majorelle Garden) is one of the few attractions in this city that has a reputation for being difficult to get tickets for. The tickets are timed and there are a limited number of entries. I had to walk to edge of the medina to hail a taxi. I got to the garden entrance without incident. However, once I arrived, getting in was another matter. Unlike most places in Morocco, where cash is preferred and is sometimes the only option, Jardin Majorelle has a strict no cash policy. All entry tickets must be purchased by credit/debit card only. But do they have any way for you to swipe your credit card at the gate? They do not. Instead you have to pay online using your phone. You can’t do it ahead of time, because tickets only become available 15 minutes before a half-hour entry time slot. Unfortunately, being located next to a giant tree-filled garden in a city with fairly weak cell service makes it rather difficult to make that online transaction without your internet connection timing out. To make matters worse, both of my credit cards didn’t trust the website and blocked my purchase multiple times, even after going through several different methods of two-factor authentication. Finally, after making an international call to my bank’s customer service, I eventually managed to purchase a combo ticket for the garden and the adjacent Berber Arts Museum. By this time, I had missed the deadline for the first time slot by 5 minutes and I thought I was going to have to wait another 25 minutes to get in. There was already a pretty long line forming outside the gate. Thankfully the security guards who had been so unmovable when it came to the payment method finally took pity on me and let me in during the first time slot.

So what was this amazing place I had to work so hard to get into? Honestly, nothing to write home about, IMHO. Jardin Majorelle is a 9,000 meter botanical garden created in 1922 by the French painter Jacques Majorelle, whose bright blue house sits at the center of the garden. The property was purchased by fashion designer Ives Saint Laurent in 1966. Laurent is buried in the garden and there is also a museum about his life and work there but I chose not to pay the additional fee to visit that museum. The garden features palm trees, cactus plants, ferns, and a variety of other plant life, along with several pools and fountains, a pavilion, and a covered bridge, all painted the same shade of blue as the house. It’s a nice place, but honestly I’ve seen much more impressive botanical gardens elsewhere, and of all the incredible one-of-a-kind marvels I saw in Morocco, this didn’t really live up to the hype for me. There was nothing wrong with it, but I just don’t understand why this garden in particular is the thing in Marrakech that people wait in long lines to get into.

My favorite part of the garden was not the garden itself, but the Berber Arts Museum, which is located inside the Majorelle house. No photos were allowed in this museum, but it featured some very interesting Berber artwork and artifacts from different times and places, along with historical information about it. The exhibit rooms are dark with hundreds of small lights shining from the ceiling to simulate the starry night sky in the desert. My second favorite part of the garden is the cafe. The cafe itself is very stylish and relaxing. Their breakfast menu lets you choose between a European breakfast and a Moroccan breakfast. I chose the Moroccan breakfast, which came with Moroccan pancakes and bread, lemonade, and mint tea. Eggs were also offered but I tend to avoid eggs. The food was delicious and plentiful.

After leaving Jardin Majorelle, I took a taxi to Koutoubia Mosque, Marrakech’s largest mosque. This taxi ride was a little more eventful than the ride here. The taxi already had a passenger in the back but still pulled over to pick me up. I knew that this was normal in Marrakech so I got in the front passenger seat. As soon as we started moving, the passenger (a 30-something woman) and the driver started arguing with each other in Arabic. I had no idea what they were saying but I could tell that the conversation was tense. I really wanted to just get out of the taxi at this point but I couldn’t bring myself to ask the driver to pull over. Every so often the passenger and the driver would grin or smirk during their argument so I gathered that it probably wasn’t all that serious. I never figured out exactly what they were saying but it seems that they were arguing over where to drop her off or maybe the route to take. In the end, she got out and didn’t seem too upset, so I think it was probably fine. I had to remind the driver to reset the meter, but he did so without argument, and took me to the mosque without further incident. The whole trip only cost me about $2.00 so I really can’t complain.

Koutoubia Mosque is an imposing rectangular stone building with a 253 foot tall minaret decorated with geometric designs. The mosque was built in the 12th century and has seen the rise and fall of many dynasties. Adjacent to the mosque is a well-landscaped park with palm trees planted in a grid pattern punctuated by benches, arched lamps, and a pavilion. As a non-Muslim, I was not allowed to go inside the mosque, but just appreciating it from the outside was more than worth it.

From the mosque, I continued on foot to the Bab Aganou Gate, one of the two original gates to the Kasbah (the fortified citadel in the historic center of the city). This intricately carved stone gate was designed as a royal entrance for the king and his family.

The mosque and the Kasbah are both on the edge of the medina, and it was a fairly short walk back to my riad from Bab Aganou. I relaxed on the riad’s rooftop patio for a while before wandering over to the Henna Art Cafe for the second day in a row. I knew that the food, the atmosphere, and the prices were all good there and I didn’t feel like putting in the time and effort to look for a new place to eat. This time I ordered the falafel platter with hummus and a side of bread and olives and it did not disappoint. To take a break from mint tea, I had a spice tea instead. This was sort of a combination lunch/dinner since it was already more than midway through the afternoon. I stayed in my room that evening, not doing much besides packing, planning, relaxing, and enjoying the fancy shower. I went to bed on the early side, knowing that I had to get up even earlier the next morning to get on the tour van that would take me to the Sahara Desert.

We’ll pick up my journey from there in a few days. Thanks so much for reading and apologies for the SIX MONTH wait! Please check out the rest of my photos from Marrakech (there are two albums). Cutting them down from over 3,000 photos to under 200 (about 100 per album) took me longer than actually writing this blog post, so I do hope you enjoy them!

You saw much more of Marrakesh than I did and your history was thorough. Curious to read of the guerrilla warfare in Tunisia.

The Algerians, too were extremely oppressed by the French and fought continuously over the hundred plus years they were colonized. Another interesting fact about the mellah is its architecture. In the mellah, balconies face the street. In the medina, they face inside toward the courtyards. Funny, I too met the last Jew in Fes. He’s never gone to Israel it seems. Thanks for sharing this. I miss Morocco.

Wow! A most interesting trip and history! I learned a lot!. Your photos are incredible! Thank you for sharing your travels with us! Your explanations are extremely thorough! Well worth the wait!

Sounds like a great start to your trip! I LOVE the tile work and it reminds me of parts of Sevilla! Thanks for sharing!

v9twph

Wohh precisely what I was looking for, regards for putting up.

This is the right blog for anybody who wants to seek out out about this topic. You understand a lot its almost arduous to argue with you (not that I really would want…HaHa). You undoubtedly put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Nice stuff, just nice!

Wonderful goods from you, man. I have understand your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely fantastic. I actually like what you’ve acquired here, really like what you are saying and the way in which you say it. You make it enjoyable and you still take care of to keep it sensible. I can not wait to read far more from you. This is actually a great website.

Rattling great info can be found on web blog.